✒ Why Now is Tuscany’s Golden Age

by Sarah Kemp

I have wonderful early memories of my father taking me, by as a young woman, to Mario & Franco’s in Soho, the upmarket “trat” – our favourite Italian restaurant (trattoria), beloved by Peter O’Toole, Terence Stamp, Jean Shrimpton, and importantly for me, my father, who was always greeted warmly, possibly due to his generous Fleet Street reporter’s expense account.

It was my first experience of great restaurant hospitality, and my very first taste of Chianti, light, astringent, and more than a little rustic. It was the 1970s, and fine wine in Britain was dominated by Bordeaux; Burgundy was still considered unreliable, Australian and New Zealand wine had not yet made their mark, and Italian wine was regarded as just a beverage to wash down pizza and pasta.

But it was in the 1970s and 1980s that the foundation for the Italian fine-wine revolution was being set, and in an ironic way, much of it was thanks to the wines of Bordeaux. Today, the wines of Tuscany are reclining alongside the great wines of Bordeaux in collectors’ cellars, and according to Liv-Ex latest data, are now even outperforming Bordeaux and Burgundy, of which more later.

Post World War II, many Tuscan vineyards had been replanted, but with poor clones which were chosen for quantity, to add calories to a war-starved nation. The principal grape, Sangiovese, was blended with others, producing simple rustic wines, and the producers knew it. As with all revolutions, you need a leader, and Tuscany found that leader in Piero Antinori, the Marchese with the piercing blue eyes, who took over the running of the family company, L&P Antinori, in 1966, and became a force for change.

Piero’s oenologist was Giacomo Tachis who had trained under the legendary Bordeaux oenologist Emile Peynaud. If Piero was the founder, his uncle Marchese Mario Incisa della Rocchetta, was the spark: while visiting Bordeaux, he was enchanted by a bottle of Château Margaux 1924, and decided to plant Cabernet Sauvignon vines at this estate, Tenuta San Guido, which was in Bolgheri near the coast, the family’s holiday estate, not in the Chianti hills, the area best known for vines. The wine, named Sassacica, and made with the aid of Giacomo Tachis, was just for family consumption, but in the late 1960s and early 1970s he was persuaded by his son Nicolò and his nephew Piero Antinori to release the wine commercially. It soon became the talk of Florence.

Then, its international reputation was increased in 1978, when it was entered into a blind tasting of international Bordeaux blends from around the world at Decanter Magazine, including classified Bordeaux growths. The judges were Hugh Johnson, Serena Sutcliffe MW and Clive Coates MW, all revered Bordeaux experts. It came top of the tasting, beating the 33 other wines from 11 countries.

Also during this period, Piero, up in the Chianti Classico hills inland, was experimenting with different blends (but based on better-quality clones of the native Sangiovese) and ageing in small barriques. With the encouragement of Emile Peynaud and Giacomo Tachis, he stopped using white grapes in the blend, which had long been a requirement for the Chianti Classico DOC. Tignanello was born, the first Super Tuscan, predominantly Sangiovese, but because it contained non-traditional varieties like Cabernet Sauvignon, it had to be classified as an IGT, the lowest rung of the Tuscan wine ladder.

Nevertheless, both Tignanello and Sassicaia, without any classification of note, sold out in restaurants at three times the price of other Tuscan wines. The Super Tuscan movement had arrived. The success and buzz around these wines galvanised the producers of Tuscany – the “quality not quantity” wine revolution had begun. Another impact of Tignanello’s success was the realisation that Sangiovese-based wines could command high prices and prestigious placements at top restaurants. Tuscany began to wake up to the potential greatness of Sangiovese, its very own grape.

The Chianti Classico Consorzio took the bull by the horns in 1987 and began a study, named Chianti Classico 2000. (Fortuitously, 1985 was the year I joined Decanter magazine, so I secured a ringside seat). Experimental vineyards were planted over 25 hectares, and the ambitious project examined grape varieties, rootstocks, planting density, yield, vine training, soil management and clonal selection. Alongside the work of the Consorzio, dynamic young producers like Paolo de Marchi at Isole e Olena were concentrating on massal selection, marking the vines which each year produced the best fruit. Overall, Tuscany’s traditional landscape was transformed, often by the new generation.

Meanwhile, a quiet revolution was occurring in Britain, beginning in the culturally energised neighbourhoods of southwest London. Italy (and those of us who plunged into the scene) was fortunate to find two extraordinary champions in the form of Nick Belfrage MW and his protégé David Gleave MW. They opened Winecellars in London and specialised in Italian wine, bringing in Isole e Olena and other top producers. Their timing was perfect – there was also a renaissance going on with Italian food. In 1987, The River Café opened in a warehouse in Hammersmith, founded by Ruth Rodgers and Rose Gray, initially serving as an employee café for architects and designers, but soon becoming popular for its pure, seasonal Italian cuisine. In the same year, Rowley Leigh opened Kensington Place in Notting Hill, with a strong Mediterranean slant, and the irrepressible and magnetic chef Alastair Little became a star in Soho; the cooking of both was strongly influenced by Italian cookery writer Marcella Harzan. All were looking for the right wines to match their exuberant food, and Nick and David were there to provide them. Young professionals (and food and wine writers, and of course me) flocked to their restaurants, and discovered there was new and considerable wine enjoyment to be found next door to France.

Over in the US in the 1970s, Darrel Corti of Corti Brothers in Sacramento California, introduced American chefs and consumers to olive oil, balsamic vinegar, Parmigiano Reggiano cheese, white truffles, and top-quality Italian wine. The US had a great affinity for Italian wine, more than the UK, but international wine reputations were now also being made in Britain, to our increasing delight.

Today, Tuscan wines are riding high in a fine-wine market which is in the doldrums. The latest Liv-Ex data makes fascinating reading. Historically, the Italy 100 index sat below the market provided by the Live-Ex 1000 and the Bordeaux 500, but in the last five years Italian prices have risen faster than Bordeaux and at times faster than Liv-Ex 1000.

What is also interesting is that Tuscany has proved to be more resilient than Bordeaux or Burgundy. In the wake of the fine-wine crash after October 2022, the Liv-ex 1000 and Bordeaux 500 fell by 28.7% and 27.2% respectively. By contrast, the Italy 100 has only fallen by 15%. The market is recognising the quality coming out of Italy after the changes put into the vineyards in the last 30 to 40 years.

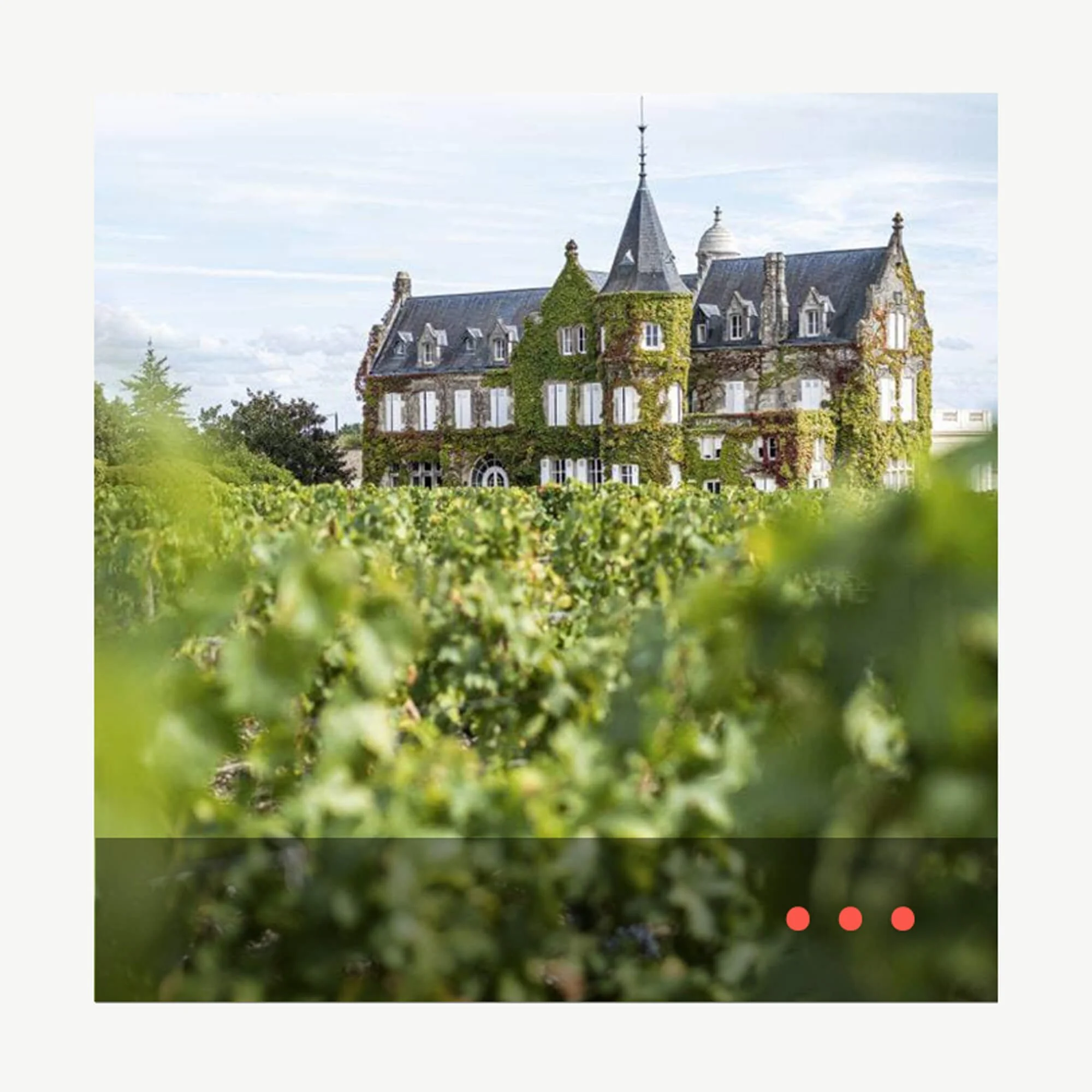

These were the reasons I wanted The Connoisseur Week to go to Tuscany, and this October Jane Anson and I undertook our inaugural trip with ten guests. After four highly successful Connoisseur Weeks in Bordeaux, the first region outside Bordeaux was an important choice. For me it had to be Tuscany – the memory and the reality today, and luckily Jane was in total agreement.

The itinerary we put together included Piero Antinori at Tignanello, Angelo Gaja at Pieve Santa Restituta, Giovanni Manetti of Fontodi, Alessandro Berlingaria at Sassicaia, Marco Balsimelli of Ornellaia, Francesco Mazzei of Castello di Fonterurtoli and relative newcomer Bibi Graetz. It was quite the week. What is clear to me is that Tuscany still offers superb value for money for world-class wine. You can still buy a Sassicaia 2020 for £300 a bottle, or the Fontodi Flaccianello della Pieve 2020 for £110. Contrast those prices with those of Burgundy and Bordeaux, and you might just realise why connoisseurs are waking up to collecting the great wines of Tuscany, recognising the vineyard expressions from the revolution in the vineyards and the splendid revolution (and revelation) of flavours, now and to come.

Here are a few of my personal favourite wines from The Tuscan Connoisseur Week 2025:

Sassicaia 1990

A wine with a legendary reputation, which delivered in spades. Made by the great oenologist Giacomo Tachis, who trained under another legend, Bordeaux’s Emile Peynaud. Glorious Tuscan perfume rises from the glass, intoxicating, a mix of crushed roses and incense. The palate has layer upon layer of savoury tertiary, hedgerow notes, dried herbs, old leather, all integrated into the waves of unctuous blackberry and damson fruit, which demands another sip. Outstanding.

Gaja Pieve Santa Restituta Rennina Brunello di Montalcino 2019 Magnum

There is an extraordinary stillness around Pieve Santa Restituta, maybe it is the aura of the church which was built in the 4th century AD. Angelo Gaja bought the property, where they have been making wine since the 12th century, in 1994, his first expansion outside the Piedmont. The vineyard sits beside the church on clay-calcareous with significant amounts of galestro soil. Beautiful succulent fruit with a breathtaking purity. There is huge depth here, wonderfully layered with a striking luminosity. Red cherry fruit caresses the palate while silky tannins hold everything seamlessly together. Just beautiful and unforgettable.

Fontodi Flaccianello della Pieve 2016

I have always been a huge fan of this estate, with the straight Chianti a regular in my cellar. The flagship is the Flaccianello della Pieve, and this 2016 is truly exceptional. Crushed musk roses on the nose, followed by intense dark plums and vibrant red fruit on the palate, lots of spice and black pepper, backed up by hedgerow notes, fine silky tannins, complex, intriguing and endless.

Ornellaia “L’Incanto” 2012

From a dry vintage, the 2012 has an ecclesiastical nose, like stepping into an ancient cathedral, incense and violets rising from the glass. The palate has yearning waves of beautiful blue fruit, gentle fine tannins gripping the melange of juicey intense fruit, wood smoke, spice and a delicious saline finish leaving you wanting to pour another glass.

Marchesi Mazzei Castello di Fonterutoli Concerto Toscana IGT 2021

Concerto was one of the first Super Tuscans, created in 1981; it was named by Marchesa Carla Mazzei as she remarked when tasting it that it reminded her of a symphony. How right she was! I have a particular affection for Concerto, which hasn’t gained quite the fame of other Super Tuscans, making it a great find for wine connoisseurs who love the more elegant expression that Tuscan Bordeaux blends can deliver. From the fabulous 2021 vintage, the wine is 80% Sangiovese and 20% Cabernet Sauvignon. There is a beautiful rich intense core of vibrant fresh black and red fruit, smoke wood, satin tannins, all showing its vineyard expression, nothing overdone, balanced and simply delicious.

Bibi Graetz Colore 2021

Bibi Graetz is an artist, and a relative newcomer to Tuscany, founding his eponymous Tuscan winery in 2000. He goes against the grain in believing the artistic hand of the winemaker is more important than terroir. Colore, made from old-vine Sangiovese grapes, has gained a following amongst collectors and it has a distinct signature, more vertical than most Tuscan wines. It is full of pure wild raspberries and redcurrants, translucent, lots of black pepper, quite Burgundian in style. Intriguing.

RELATED POSTS

Keep up with our adventures in wine

Sarah Kemp discusses the reasons why Tuscany is outperforming Bordeaux and the rest of the fine wine market.